The White forces captured Tampere on April 6, 1918, after two weeks of intense fighting. Once the battles ceased, the victors began settling scores with the defeated. Even over a hundred years after these events, many misconceptions persist regarding the punitive actions following the city’s capture. However, the events and the victims of the executions are fairly well documented, excluding those shot during the actual battles. For the latter, it is somewhat impossible to determine who died in combat and who was executed instead of being taken prisoner.

The events following the capture of Tampere are fairly well known from April 8th to 9th. During these days, the first clearly selective executions of prisoners took place. Since there are no known identifiable executions from April 7th, it can be assumed that the shootings at that time were limited to isolated cases. The selected Red Guard leaders began to be executed only from April 8th to 9th onwards, and they were not picked for execution from the lines of prisoners standing in the Central Square immediately after the city’s capture. In Tampere, the executions were preceded by a 2–3-day process of selecting those to be shot, whether one calls it a field court or something else is up to debate.

In total, just over 200 people were executed in Tampere after the city’s capture. There are stories in local folklore of prisoners being shot at locations such as the sheet metal warehouses, near the Tammerkoski railway bridge, somewhere in the vicinity of the Tampere Theater or the Frenckell area, and even at the lower reaches of Tammerkoski. In these cases—aside from the sheet metal warehouses—it is likely that some of the executions occurred either during the capture battle or immediately afterward. In some instances, it is probably a case of unreliable rumours that have been passed down by those recalling the events later. In any case, these early acts of violence did not involve widespread executions.

The executions at the sheet metal warehouses, on the other hand, can be definitively documented, although in most cases, the victims have remained unidentified. It is now known that some of the information related to the executions at the sheet metal warehouses is inaccurate. For instance, the executions of Russians that took place there have been somewhat exaggerated. Not all Russians held at the warehouses were, in fact, shot, as there is evidence that even when the warehouses were being emptied of prisoners, some of the Russians were transferred out alive.

Fate of the Russians

One of the most persistent misconceptions concerns the fate of the Russians in the city. At the time of the capture, there seem to have been at most a couple of hundred Russians in Tampere—fewer than often reported. In this context, “Russians” refers not only to Great Russians but also to representatives of the empire’s minority nationalities. The group of Russians who remained in the city consisted of officers and their families, medical personnel, and a small number of regular soldiers.

Most of the soldiers had left Tampere when the Russian army was demobilized in the spring of 1918. At this point, the Russian barracks located in Kalevankangas had also been taken over by the Red Guard. After that, the Russian soldiers no longer had proper accommodations in the city. The few soldiers who remained in the city had to settle in the housing provided by the Red Guard or in private apartments. They were not present in large numbers in either location, though some non-commissioned officers and soldiers stayed to continue training the Red Guard, while others resided in the city with their Finnish spouses. Finding a place to stay was not easy for these spouses either, as they were almost exclusively living with working-class women who were living as subtenants.

The medical personnel who served with the Reds lived either at their assigned locations in various schools or in accommodations arranged for them by the Red Guard. The officers, on the other hand, lived in private residences, which proved to be their salvation. Most of the officers had come to Tampere either shortly before or during World War I. Being speakers of European lingua francas, they had managed to establish connections with the local intelligentsia by the time the Civil War broke out. Since the officers, with few exceptions, did not join the service of what they viewed as the vulgar Red regime, they were generally safe from White retribution due to their connections with the local upper class. Unlike in Viipuri, where the White forces carried out ethnic cleansing during the capture of the city at the end of April, the Russian elite in Tampere did not face the same fate. The White forces generally treated Russian medical personnel properly, and they were safe from executions.

Most of the Russians who had joined the Red Guard and were present in Tampere during the battle for the city left with two groups of guards who broke out of the city at the last minute. These Russians had few illusions about their fate at the hands of the victors, especially since the Whites had announced in their proclamations that Russians who joined the Reds would be shot.

Regarding the Russians, after the capture of Tampere, the Whites’ purges were almost exclusively directed at soldiers who had fought in the ranks of the Reds or Russians who were believed to have committed acts of robbery or similar offenses. A thorough investigation was conducted for officers if there was reason to suspect they had served with the Reds. Ultimately, this investigation was carried out by the military court of the White Western Army, led by Major General Martin Wetzer. It is known that this court investigated at least two cases involving Russian officers. Cavalry Captain Sergei Davy was acquitted by the court, whereas Lieutenant Colonel Georgi Bulatsel was sentenced to death.

A small number of Russian officers were held as prisoners by the Whites after the capture of Tampere, but both Wetzer and Commander-in-Chief Mannerheim advocated for their release. Eventually, all the officers were freed. Nearly all the Russian officers, along with other remaining Russian prisoners, were transported by sea back to Russia or other parts of the disintegrating empire via Helsinki during the spring or early summer of 1918. In total, it appears that around a hundred people were sent from Tampere to Russia.

Lieutenant Colonel Bulatsel was an exception among the officers. The Whites knew that he had participated in the Reds’ military leadership, so his execution was, in that sense, a logical outcome. However, it might have been a surprise to Bulatsel himself. During World War I, even captured officers were treated as gentlemen, held in special prisoner-of-war camps for officers, where conditions and treatment were generally quite good. It’s possible that Bulatsel believed in this kind of system, which might explain why he didn’t flee Tampere when he had the chance. He might have seen himself more as a soldier fulfilling his duty rather than a revolutionary joining the rebels. However, the Whites saw it differently. After the death sentence was pronounced, it was reported that Bulatsel requested a meeting with Martin Wetzer or the White Army’s Commander-in-Chief Mannerheim, but his request was denied. Bulatsel was executed early in the morning on April 28th.

The executed and their selection

Executions were carried out in Tampere over a span of two months. In the early days, executions occurred almost daily. During the first week alone, from April 8th to 15th, about 50 prisoners were shot. A clear criterion for these executions was, in most cases, a high rank within the Red Guard or the Red administration. At this stage, those executed included battalion commanders and company leaders of the Red Guard, members of staff, the local head of the Red prison administration, the city’s chief of artillery defence, a prosecutor of the revolutionary court, and others. Many of the victims were from the nearby countryside, with a notable number from Orivesi. Information provided by local Civil Guard units from the surrounding areas was clearly used in selecting those to be executed. On the other hand, leaders of the Tampere Red Guard generally avoided these early executions.

When discussing the executions, it’s important to note that the executions in Tampere and Messukylä cannot be separated from one another. At least in the early stages, the primary execution site for prisoners gathered in Tampere was in Messukylä, where the prisoners were transported by rail and then marched to the execution point on foot. The exact location of later executions is not well documented, but they may have occurred near the Kalevankangas cemetery. In April, individual prisoners were still being shot almost daily, but by May, the executions became more organized. The sporadic shootings gave way to more systematically selected executions involving larger numbers of victims.

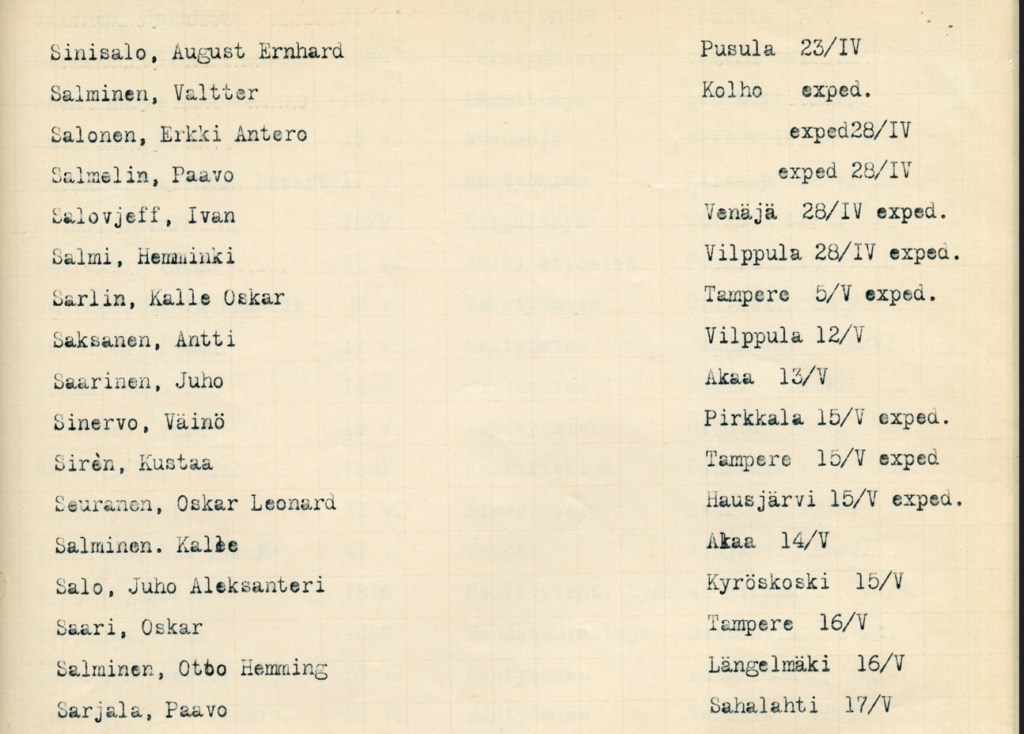

The executions in Tampere culminated in six mass executions, during which nearly 100 Reds were shot—meaning that almost half of all executed prisoners met their end in these mass executions. In three of these cases, the executions were at least partly carried out—possibly even led—by Civil Guard units from nearby areas. On April 14th, 15 prisoners were shot, all but three of whom were from Orivesi. The purge on April 20th was conducted by the Civil Guard from Kuru, during which 31 prisoners were shot, 27 of whom were either from or active in Kuru. On April 23rd, the leadership of the prison camp allowed the Civil Guards to carry out one more purge. Based on selections made by the Civil Guards from Vilppula and Kolho, 19 prisoners were executed.

The executions led by the Civil Guard all occurred while Gustaf Adolf Finne was the commandant of Tampere. However, the final mass execution took place on the same day Finne left his position. Undoubtedly, this execution also had Finne’s approval. When Finne departed on April 23rd to prepare for his new role as the commandant of Vyborg, Captain Carl Gustaf von Kraemer became the new commandant of Tampere. During his tenure, the executions took on a more systematic nature compared to Finne’s time. While Finne had allowed executions based on the personal hatred and arbitrariness of various local Civil Guards, von Kraemer, as a former police official, is considered to have attempted a more selective approach in choosing who would be executed.

Nevertheless, the command in Tampere cannot be seen as becoming much more lenient during von Kraemer’s time. During Finne’s slightly more than two-week tenure as commandant, approximately 120 prisoners were executed. Under von Kraemer’s command, another 90 prisoners were executed over the course of a month and a half.

The head of the prisoner-of-war system, V. O. Juvelius, prohibited the transfer of prisoners into the hands of the Civil Guards at the beginning of May. This decision was largely followed in Tampere, and executions effectively came under the commandant’s control. After this, there was less room for the irrational violence of the Civil Guards. However, mass executions continued. One sign of the more systematic approach was the gathering of prisoners at the main guardhouse of the Kalevankangas prison camp before execution.

The significant decision-making power of the commandant is also evident from the fact that some executions were carried out clearly against the opinions of the investigating judges responsible for prisoner investigations. It seems likely that in these cases, the commandant made his own, final conclusions. Von Kraemer’s choices are clearly reflected in three mass executions carried out during his tenure. Among the 24 prisoners executed on April 28, several had been involved in confiscations or outright robberies committed by the Reds. Some of the executed also had previous criminal records. Even more clearly, a criminal background was the apparent basis for execution in the case of those shot on May 5. This time, 24 were executed. Among the victims were also a few Red Guard leaders from Tampere.

The last major execution took place on May 15. The group to be executed was diverse, including a few Red Guard leaders and some individuals involved in crimes. It was clear that during his tenure, von Kraemer aimed to eliminate the most prominent and hated Red Guard leaders, as well as largely those he considered criminal elements.

The final prisoners were executed in Tampere in June 1918, by which time executions were already scheduled to cease. On June 8, five prisoners were shot: four Russians and one Finn. The very last execution occurred on June 20, when a person named Martti Heribert Hurme from Tampere was shot. His crimes were reported to include involvement in grave robbery.

What was the composition of the group of just over 200 people executed in Tampere? Among those executed, 28 individuals were known to have served in Red Guard staff positions, as company commanders, or in even higher positions, representing less than 15 percent of the victims. At least sixteen of those executed were Russian, and fewer than ten others had held positions in the Red administration. Together, these groups account for just under a quarter of all those executed. The remaining three-quarters were ordinary Red Guards or at most platoon leaders.

Since it is presumed that many of those executed by the Civil Guards in Tampere had incurred the community’s wrath by participating in confiscations and home searches, this factor—combined with the individual’s prior criminal background—appears to have been the most common reason for the execution of an individual in Tampere in the spring of 1918.

Tampere as part of the bigger picture

In the aftermath of the Civil War, according to current information, the Whites executed about 7,750 Reds. How does Tampere fit into this overall picture? Preceding the surrender of the Reds in Tampere, the largest battle in Nordic military history so far had taken place, with 800 Whites and 1,200 Reds killed. The Whites immediately captured over 8,000 prisoners after the fighting ended. Later, more prisoners were gathered from the city, but at the same time, others were released based on various recommendations. Paradoxically, among those released early were some who might have been expected to be at significant risk of execution later. However, the recommendations from local bourgeoisie of Tampere differed significantly from the views of the city’s commander, who was responsible for securing the occupied areas. The Reds released early were done mostly on the recommendations of the more lenient bourgeois.

Tampere became a significant site for executions, but it was overshadowed by a few other cities later captured by the Whites. In Lahti, Vyborg, and Valkeala, there were significantly more executions than in Tampere. In Lahti, the Whites executed over 700 prisoners; in Vyborg, 370 Finns alone; and in Valkeala, about 290 people. Slightly over 200 prisoners were also executed in Hollola and Lappee/Lappeenranta. In most of these places, the Whites had captured thousands of prisoners or had gathered them there soon after the fighting ended.

Tampere differed significantly from both Lahti and Vyborg as an execution site. In Lahti, 200 women were killed, almost all of whom had fought with weapons in hand. In Tampere, there were over 300 armed women. Some of these women quickly abandoned the fight and avoided capture after the city surrendered. However, a large number of armed women also remained in Tampere and were captured. It is possible that some of these individuals were executed, but there is no evidence to support this. It is known with certainty that only two women were executed in Tampere. In both cases, the women refused to separate from their spouses who were sentenced to execution and faced death together with them.

Another difference concerns the treatment of Russians. When the Whites captured Vyborg, an ethnic cleansing was clearly carried out against the city’s Russian population, including women. Tampere did not experience such an ethnic purge; instead, after the city’s capture, the executions primarily targeted Russians who had fought in the Red ranks.

After the Civil War, the executions generally required the support of the local population to be carried out. With this support, the violence of the occupying forces could escalate to unpredictable levels. In Tampere, the Red administration had acted relatively moderately, and therefore, its representatives did not face the same level of animosity after the city’s capture as was seen in many parts of Southern Finland. The most hated Reds in Tampere were likely the leaders of the Red Guards’ pioneer battalion, who had forced the city’s bourgeoisie into labour. A similar moderate attitude towards local Reds was also observed in Pispala and Messukylä, which were part of Pirkkala.

The moderate attitude of Tampere, Pispala, and Messukylä residents towards their local Reds is evidenced by the local numbers of those executed in Tampere. The purge was relatively harshest in those municipalities whose local defence forces had received more or less free rein from the city’s commander soon after the capture. Among the over 200 people executed in Tampere, there were 33 from Kuru, 22 from Orivesi, 17 from Keuruu, and 15 from Vilppula. In contrast, despite having a population many times larger, 54 Reds from Tampere were executed, 13 from Pirkkala, and only one from Messukylä.

The executions in Tampere are a dark chapter in the city’s history but had the city dwellers and suburban residents given their anger as much power as in many other parts of Southern Finland, the consequences might have been even more devastating.

Sources

Hoppu, Tuomas: Toivon ja epätoivon aika – Tampereen vankileiri 1918 ihmiskohtaloineen. 2020.

Hoppu, Tuomas – Nieminen, Jarmo – Tukkinen, Tauno: Sisällissodan taistelut. Kaatunut. Kadonnut. Teloitettu. Latvia 2018.

Raevuori, Yrjö: Kaupungin kohtalokas kevät ja kesä. Porvoo 1960.

Tikka, Marko: Kenttäoikeudet. Välittömät rankaisutoimet Suomen sisällissodassa 1918. Helsinki 2004.

Tukkinen, Tauno: Punaisten teloitustappio 1918. Helsinki 2013.

PhD Tuomas Hoppu is a historian living in Pirkkala, who has written extensively on various aspects of history. He was part of the research group of Vapriikki’s original Tampere 1918 exhibition.