The defensive activism of Finnish women can be seen as having begun during the Russification periods at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, when women began to engage in so-called passive resistance by founding a women’s kagal, following the example set by men.

Around the turn of the century, women participated in collecting signatures for the Great Petition addressed to the Russian Tsar, as well as in the smuggling of propaganda leaflets and weapons. Women also actively supported young men who sought to become Jägers in Germany during 1915–1916 by operating secret routes throughout Finland and by sending them supplies to the battlefields of the First World War.

The more organized and extensive national defence activities of bourgeois-oriented women began with the establishment of the Civil Guards in the autumn of 1917. As recently as the spring of that same year, women from both the bourgeoisie and the political left shared a common concern about the country’s social situation, but goodwill alone was not enough to sustain cooperation across party lines. The nation was becoming sharply divided and sliding toward war. Women, too, chose their sides. Women’s associations such as the White Ribbon, ladies’ societies, the Finnish Women’s Association, the Finnish-speaking Women’s Association, and the Martha Organization gave their support to the White side. Relief efforts were often channelled locally either at their initiative or through them. A joint declaration by bourgeois women’s organizations emphasized patriotism and self-sacrifice—values that would later be reflected in the ideology of the Lotta Svärd organization.

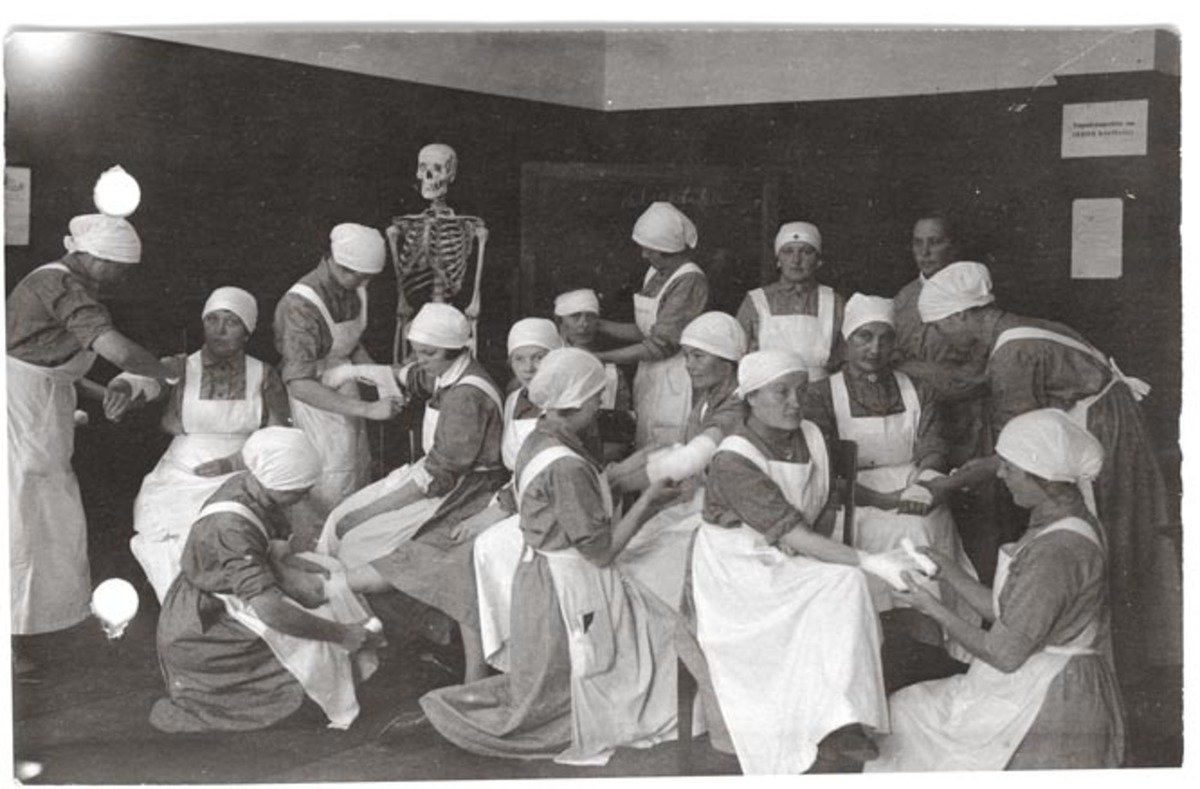

During the Civil War, the most important role of women on the White side was to support the troops by providing food, acquiring supplies, and offering medical care. This work was typically organized through local women’s associations or initiated by the Civil Guards. The wartime efforts of White-aligned women formed a clear foundation for the Lotta Svärd organization, which was established a little over a year after the war. Many of the principles and practices of the Lotta Svärd movement—such as the unarmed status of women and their responsibility for caring for the deceased—were already defined during the Civil War.

After the war, the women who had supported the White side received recognition from Commander-in-Chief Mannerheim in his speech at the victory parade in Helsinki.

“On the battlefield as sisters of mercy or as Lotta Svärds, or tirelessly working at home to equip and feed the soldiers—everywhere, in all areas, Finnish women have worked silently and humbly, forgetting sleep and rest.”

War Marthas and Local Sewing Circles

After the Civil War, nationwide defence activities by women came to a halt for a time, but in Karelia, the War Marthas—marked by a green cross—continued their efforts. The War Martha organization, established during the war with the support of the White government in Vaasa, was composed of trained volunteers, primarily teachers. With backpacks on their backs, the War Marthas travelled from town to town cleaning up, alleviating famine, and helping families start anew in Karelia. Their operations ended at the turn of 1918–1919, but they are regarded as a precursor to the Lotta Svärd organization.

In Southwest Finland and Satakunta, the Civil Guards were the first to reorganize after the Civil War. As their activities began to recover in the summer of 1918, women also became active once again. Initially, sewing circles were established to support local Civil Guards. Women who had already supported the Civil Guards during the Civil War were especially involved. The primary activity of these early sewing circles was producing various types of equipment for the local Civil Guards. The motivation of the women who joined often stemmed from personal experiences during the war—such as living under Red occupation or witnessing the advance of the White Army.

The local women’s divisions supporting the activities of the Civil Guards had various names during the years 1918–1919. The first to use the name Lotta Svärd were Helsingfors Skyddskårs Lotta Svärd Avdelning no. 1 and Riihimäen Lotta Svärd. The daily order issued by the Civil Guards’ Commander-in-Chief, Didrik von Essen, is considered the founding document of the Lotta Svärd organization. On August 29, 1919, he declared: “Women in Finland also have a duty to support the Civil Guards. This duty can best be fulfilled by forming Lotta Svärd associations.”

The name Lotta Svärd was commonly used starting in 1920. Initially, members were called Lotta Svärds—later simply Lottas. The name was intended to give women’s national defence efforts a noble and martial heritage. In Johan Ludwig Runeberg’s epic poem The Tales of Ensign Stål, Lotta Svärd, who gave her name to the women’s activities within the Civil Guards, was the wife of a soldier, acting as a caregiver and mother figure to the troops. It is telling that the name for the organization was given by the Civil Guards’ headquarters. According to Annika Latva-Äijö, who has studied the early stages of the Lotta Svärd, the name also helped to invent and establish a tradition of women’s participation on the battlefield. Importantly, the name clearly tied the organization to war and national defence.

“Women in Finland also have a duty to support the Civil Guards. This duty can best be fulfilled by forming Lotta Svärd associations.”

Didrik von Essen, Commander-in-Chief of the Civil Guards

The National Lotta Svärd Organization

Despite women’s active organizing and enthusiasm for national defence, the establishment of a nationwide association was a complex process. The administrative structure was finally completed in February 1921, even though Lotta Svärd had already been entered into the association register a year earlier. A long and multifaceted dispute arose over the bylaws.

Following the order from the Commander-in-Chief of the Civil Guards, the first set of bylaws for Lotta activities was drafted by Ernst Knape, head of the General Staff’s Sanitation Division, but they were almost unanimously rejected. After that, various groups across the country began drafting their own bylaws according to their own interests. In the early stages, the bylaws of the Pori association proved to be the most popular, characterized by a strong desire for joint organization with the Civil Guard. However, the leadership of the national Lotta Svärd was much more in favour of a more advanced form of separate organisation from the Civil Guard, than were the numerous women involved locally in the voluntary national defence movement.

As a result, not all local associations accepted the first national bylaws agreed upon in 1921. As many as one-third of local Lotta Svärd associations refused to join the national organization after the bylaws were published. In addition to the emphasis on a distinct organizational structure, opponents were also wary of the new organization’s pronounced military character.

In the spring of 1922, the organization’s central executive committee was forced to ease the application of the rules. At the local level, the division into sections was no longer required, nor was the separation between support Lottas and active-duty Lottas. By the mid-1920s, Lotta Svärd had truly begun to evolve into a nationwide women’s defence organization with a centralized leadership. This transformation was solidified by the adoption of new rules in 1925, a reform of the training system, and the publication in 1926 of the Golden Words—the “Ten Commandments” of the Lottas, which became deeply significant for the members. Local associations also gradually began to join the national organization. The full unification was not completed until 1927, when the last “rebellious” local association, the Launonen Lotta Svärd Association, finally joined the national Lotta Svärd organization.

Nevertheless, the grey Lotta uniform remained largely unchanged from 1926 until the organization’s dissolution. Throughout its existence, the uniform was occasionally criticized, especially under the harsh frontline conditions during wartime, where it was often seen as impractical and cumbersome. Despite this, over time the Lotta uniform became an important symbol of unity within the organization.

Why the Lottas Became a Separate Organization

The First World War transformed the position of European women politically, socially, and culturally. In Finland as well, the old gender order—according to which a woman’s place was primarily in the home—had begun to gradually change from the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries as part of the broader process of becoming full citizens. This shift gave women new opportunities to act more independently than before, bringing with it a certain element of autonomy from men and marriage. Women who had participated in the Finnish Civil War also demonstrated that the role of women was changing.

The women on the White side of the Finnish Civil War did not, however, seek to challenge the prevailing gender order, which defined a woman’s role primarily as a maternal caregiver—even under frontline conditions. This understanding of women’s proper function, and the perceived unsuitability of military action for women, was emphasized not only during the war itself, but especially as the Lotta Svärd associations began their activities.

As Tyyne Söderström from Pori wrote in the Suojeluskuntalainen magazine in 1921:

“Surely it is not the central executive committee’s intention that women, too, should begin serving at the front as organized units? Women have never participated in wars, except when war has, for one reason or another, descended into the movements of rabble, and when women have formed their own companies—as, for example, during the War of Independence in the Red Army, in the Bolshevik army, or during the French Revolution in Paris—they have universally evoked disgust or ridicule in any thinking person. In war actions, women only get in the way of men and cause confusion and disorder. The only role a woman has on the battlefield is the noble duty of a nurse, and this function has always been organized by the military’s top medical command.”

Within the Civil Guard movement, it was understood that there was no going back to the old ways. Already in 1918, Suojeluskuntalainen warned that women, having experienced the upheaval of war and recognized their own capabilities and skills, might not be willing to return to their former roles or surrender the positions they had attained during the war to men. By bringing women visibly alongside the Civil Guard, their increased opportunities and the changed postwar conditions were acknowledged. At the same time, however, there was a clear intent to guide women toward the “right” ideology, the “proper” place, and to maintain control over their activities.

Already in the early 1920s, the Lotta Svärd organization was formally an independent women’s auxiliary group, but its clearer role in national defense only took shape—and was shaped—over the years as the organization grew. As its operations and training system developed, Lotta Svärd became practically ready to support the Civil Guard in the event of war. During the formation of the national organization in the early 1920s, the Suojeluskuntalainen magazine took a very clear stance on the place and purpose of the Lottas:

“The Lotta Svärd associations were originally founded for the Civil Guard, not for themselves, and they should remain that way. They must be closely connected and in cooperation with the Civil Guard—only then can they carry out the work that belongs to true ‘Lotta Svärds.’”

Many women also did not automatically seek a separate organization of their own; instead, they wished to work in a shared organization alongside men, as the women’s sections of the Civil Guard. In the early stages of organizing, both men and women often viewed cooperation in the field as more important than separation. At the turn of the 1920s, the Finnish tradition of joint civic organization was still strong, so women naturally took their place alongside the men of their own social class, within a life sphere defined as feminine.

The Lotta Svärd significantly increased the degree of separate organization among women in Finland, and women's confidence in forming their own groups grew. This change was especially profound in the lives of rural women.

The Civil Guard and the Lotta Svärd formed a paired organizational structure that operated in close cooperation. Women and men worked side by side for the same cause, although within their own separate organizations. Both the Civil Guard and the Lotta Svärd saw their mission as one of unifying the “nation” after the Civil War. In the 1920s, the majority of the “people” still lived in rural areas, and the rural population had mostly proven loyal to the White cause during the conflict. Therefore, a model of cooperation based on rural male–female working partnerships naturally took on a central role within both the Lotta and Civil Guard organizations, especially if the goal was to rally as broad a base of the population as possible behind voluntary national defence.

This approach was also influenced by the rural tradition of joint civic organization, visible for example in the activities of youth associations, where both genders were included in shared endeavours, with attention to their differing roles and aptitudes. Furthermore, as agriculture modernized, farmers’ associations began to lose their function as unifying general-purpose organizations in the countryside. Taking their place—sometimes even competing with them—were often the Lottas and Civil Guards, which represented the era’s “fashionable” patriotism and offered a form of participation that distanced itself slightly from everyday labour-focused organizations.

When the Lotta Svärd was founded, its primary mission was defined as awakening and developing the Civil Guard spirit and assisting the Civil Guard in protecting the home and the homeland. Women were thus given a supportive role to the work of men.

The Civil Guard soldier needed a wife and companion by his side in order for the resources of the White nation to be directed toward a common goal and to defend against a shared enemy. The role of the Civil Guard soldier’s wife was to be clearly defined, and she was expected to find the right way to contribute to the common cause. She was thus seen as an active participant, not merely a passive follower.

From the very beginning, however, gender differences shaped the organization of activities, and women’s tasks were consistently based on maternal care and nurturing, regardless of the organizational structure. The Lotta Svärd significantly increased the degree of separate organization among women in Finland, and women’s confidence in forming their own groups grew. This change was especially profound in the lives of rural women, marking their entry into the “agrarian public sphere.” This trend is reflected in all three major and successful women’s organizations of the interwar period: the Martha Organization (Martat), the Agricultural Women (Maatalousnaiset), and the Lotta Svärd.

Despite resistance, the path ultimately led to the creation of separate women’s organizations. This was largely due to the influence of key Lotta Svärd figures such as Hilja Riipinen, who had been active in the early women’s rights movement, and more broadly, as a sign of respect for bourgeois women’s associations that had been instrumental in organizing the logistical support for the White Army. Among educated women, there was a desire to uphold the idea of progress. If women had been merely “subordinated” as a branch of a broader national defense organization, this would have signaled regression to a significant portion of the support base—particularly to influential women activists within those associations.

Although the women’s national defense movement initially arose spontaneously across the country, it was soon organized into a formal structure by urban, educated women. For them, separate organization was from the very beginning the most suitable form of action, and in their view, it advanced the status of (bourgeois) women.

On the other hand, separate organization also suited the interests of the Civil Guard. It allowed for a clear and emphasized—but culturally acceptable—way of defining the woman’s place and role within Finnish voluntary national defense, as well as in building a new, post-war society governed by the victors. The goal was to make full use of all those inspired by the Civil Guard ideal—men and women alike.

Bibliography

Ilvonen Mirva 2002. Varustajia, lipuntekijöitä, ruumiinpesijöitä – Valkoiset naiset Suomen sisällissodassa 1918. Master’s theses, University of Helsinki, Department of history.

Latva-Äijö, Annika 2004, Lotta Svärdin synty. Järjestö, armeija ja naiseus 1918-1928, Helsinki: Otava.

Lukkarinen Vilho 1981, Suomen lotat. Lotta Svärd-järjestön historia, Helsinki WSOY.

Nevala-Nurmi Seija-Leena 2012, Perhe maanpuolustajana. Sukupuoli ja sukupolvi Lotta Svärd- ja suojeluskuntajärjestöissä 1918-1944. Tampere: Tampere University Press.

Nevala Seija-Leena 2019, Lottapuku naisten maanpuolustusidentiteetin rakentajana ja ylläpitäjänä. Teoksessa Säädyllistä ja säädytöntä. Pukeutumisen historiaa renessanssista 2000-luvulle. Toim. Anna Niiranen ja Arja Turunen. Historiallinen arkisto 150. Helsinki, Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura.

Sulkunen Irma 1991., Retki Naishistoriaan, Hanki ja jää, Helsinki.