The Finnish Civil War in 1918 was not only a war fought by men, but it affected women in many different ways. Women had to send their husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons to war. There was deep concern over the fate of those who left, and at home, they had to manage without their contribution to work.

In addition to these new responsibilities that accumulated at home, the war also changed women’s roles in other ways. Some women were inspired by the ideology of their side and decided to support the army’s efforts in various ways. This happened on both the White and the Red sides.

White women

In the autumn of 1917, women’s divisions were established within the Civil Guard (Suojeluskunta) with the purpose of providing food for the men’s training exercises. During the winter, these women’s divisions also began to receive nursing training. When the Civil War broke out, women with experience in provisioning and nursing were needed by the White Army at the front. Some of them went along with the Civil Guard troops, but they were also needed behind the front lines in hospitals and in civilian areas, providing food as soldiers moved in large groups from one staging point to another.

Photo: Ostrobothnian Museum.

At the beginning of the war, women’s activities were primarily the efforts of local volunteers. However, in February, this work began to be systematized with the establishment of a national supply corps. Women were called upon in newspapers to participate in patriotic work suited to them, such as lodging, provisioning, clothing, and nursing. Women also performed various secretarial duties. Sewing flags was also considered a women’s task and was regarded as a true honour.

As the fighting began, women were entrusted with the emotionally heavy responsibility of washing the bodies of the dead and accompanying them to burial. In hospitals, there was a need for many assistants:

There were not enough trained nurses, and therefore a number of assistants were recruited. Some of them served as comforting and encouraging sisters to the wounded. They helped with food service, combed and washed the patients, and took care of their errands. They had to handle promissory notes, do shopping, and procure newspapers and books. Above all, they had to manage the patients’ correspondence.

White Book, 1928, p. 195

Photo: Varkaus Museum, A. Ahlström Corporation collection, photographer Ivar Ekström.

When the Whites realized that the rebellious Reds could not be subdued with just volunteer Civil Guard troops, the government issued a declaration on February 18, 1918. In it, every law-abiding citizen of conscription age was called to arms in defense of the homeland. This declaration was interpreted in a way the government had not anticipated. Young women, tired of just cooking and sewing, volunteered for military service. In both Savo and Ostrobothnia, young women requested to be admitted to weapons training.

The commander-in-chief of the White Army, Mannerheim, immediately rejected these ideas, stating that nursing and logistical support were the responsibility of women, and that combat was “exclusively a man’s right and duty.” Conservative women’s associations also expressed unified opposition in newspapers, declaring it would be shameful for Finnish women to, out of thoughtlessness or a desire for adventure, start forming female military units in the style of Russia.

After this, the small female units that had already been formed were disbanded, and training efforts were abandoned. A few individual women did manage to make it to the front carrying weapons alongside men. However, they were exceptions, and according to the official stance, their actions were prohibited.

Photo: Uusikaupunki Museum, photographer Augusta Olsson.

Women’s ability to participate was significantly influenced by which side of the front they were on. In southern Finland, controlled by the Reds, women who supported the Whites had to operate in secret. This created a need for female spies and smugglers. These rarer roles were particularly taken on by young female university students. The most famous female smuggler to gain notoriety after the Civil War was Verna Eriksson.

During the Civil War, 24-year-old Verna Eriksson wanted to take part in supporting the White Army. This engineering student, studying physics and chemistry at the University of Helsinki, was not content with secretly knitting mittens or socks in the Red-occupied city—she wanted to do something bolder and daringly audacious. Verna began smuggling weapons and ammunition together with her fellow student, Salme Setälä.

Their actions were extremely risky, and they didn’t even tell their own family members. The operation was strictly secret, and code names were used for assignments. Verna operated under the alias Peija. The young women smuggled weapons by hiding them under their winter clothes or in baby carriages and boldly transported them in broad daylight right under the noses of Red Guards and Russian soldiers. None of the female students known to have smuggled weapons were ever caught.

After the war, both Verna and Salme were awarded the Cross of Liberty by Mannerheim in recognition of their brave service for the homeland. However, Verna’s story ended tragically that same autumn, as she died of cancer on October 16, 1918.

White women were not paid for the work they performed. Generally, they came from well-off families, so financial compensation was not necessary. This highlights the fact that, on the White side, women participated in the activities driven by ideological motivation.

Photo: Finnish Heritage Agency, Journalistic Photo Archive Otava.

Red women

At the turn of January and February 1918, the Red Guard called on women to take on the same support and nursing duties as on the White side. After seizing control of Helsinki, the Red Guard took over the Bank of Finland and promised to pay wages to both soldiers and women supporting the army. The wages were high—for example, a woman who transferred from a co-op office to serve as the treasurer of the Red Guard’s provisioning committee received double the salary in her new position.

The appeal of working for the Red Guard was also because, with the outbreak of war, many industrial plants had to shut down, leaving women unemployed. Thousands of women sought these well-paid jobs, but there weren’t enough positions for everyone. The Red leadership decided that jobs should be offered primarily to women who had long been members of the labour movement, rewarding them for their loyalty to the cause.

For many, ideological enthusiasm, in addition to money, was a motivation to support the Red Guard’s activities. Sometimes, women were encouraged by their own families to join the Guard, as the male family members were often already serving as soldiers, while the women typically worked in support and nursing roles.

Photo: Satakunta Museum, photographer John Englund.

On the red side, women were also accepted into respected administrative roles. For example, Hanna Karhinen and Hilja Pärssinen served in the People’s Delegation of Finland, which was the revolutionary government of the Reds. Women also participated in local Red revolutionary tribunals, which took over the functions of municipal and district courts in areas controlled by the Reds.

Many young women were left without the coveted jobs in the Red Guard. Among them arose the idea that they could participate in the Guard’s activities by taking up arms, just like the men. After all, there had been female soldiers in Russia, so they did not have to look far for inspiration. However, the Red leadership disapproved of the idea, and even the Social Democratic women’s associations strongly opposed female Guards.

Official decision-making stalled for so long that, by the time the Workers’ General Council of Finland banned the arming of women on March 2, 1918, some women’s units had already been formed. As a result, the People’s Delegation ultimately reached a compromise: the already established female units would not be disbanded, but they would be kept in reserve. At first, women were used in guard duties, but as the war progressed and turned against the Reds, women were also sent to the front, and more women’s units were established during March.

In total, approximately 2,400 women joined about 30 women’s units, though not all of them took part in combat. It is also estimated that around 200 women took up arms in addition to their regular duties, especially during the retreat phase. The women in these units were very young—only about a third of them were over 20 years old. The youngest were just 13-year-old children. It was precisely this youthful fervour and enthusiasm that encouraged young women to join the Guard, support the Red cause, and defy old-fashioned conventions and expectations.

Although the women’s units did not have significant military importance due to their relatively small numbers—the Red Guard’s total strength was around 100,000—the participation of women held symbolic significance. Especially in the final stages of the war, it was emphasized that men could not retreat if even the women dared to hold their ground on the front lines.

Approximately 60 female soldiers were killed in battle, and an estimated 70 women who served in support and medical roles also lost their lives. After the fighting ended, 260 armed women were executed, along with 190 other Red women. These figures are not exact, as not all of the deceased may have ever been found.

Photo: Lappeenranta Museum, Wiipuri Museum Collection.

Retreat toward the east and women in prison camps

When defeat seemed inevitable, the Reds began fleeing eastward with the intention of crossing the border into Soviet Russia. Women and children also joined the long columns of escapees, as many soldiers took their entire families with them since returning home appeared highly uncertain. Among those fleeing were both women who had been on the payroll of the Red Guard and women who travelled solely as refugees following their husbands. Some managed to cross the border, but the majority were captured by the Whites at the beginning of May. A large mass of prisoners was apprehended near Lahti, and on the Fellman Field more than 20,000 captives were held for several days before being transferred to prison camps. Altogether, about 80,000 people suspected of being Reds were captured across Finland.

Photo: Helsinki City Museum, Photographer: Ivan Timiriasew.

In the prison camps, women usually had to wait for their cases to be processed anywhere from two weeks to over four months. During the preliminary investigation, efforts were made to determine the level of threat posed by each prisoner; those deemed least dangerous were sent back to their home districts to await trial. Those suspected of more serious crimes remained imprisoned while additional information was requested from their home communities.

Conditions in the prison camps were harsh. The facilities were overcrowded, and opportunities for washing were poor, allowing lice and the diseases they carried to spread quickly. The food situation in the camps was abysmal, and hunger-weakened prisoners were highly susceptible to illness, dying even from diseases that would not have been fatal under normal circumstances.

Women, however, survived in the prison camps considerably better than men, and mortality among them was low. There are several reasons for this. First, it is thought that women took better care of their hygiene. In addition, women’s caloric needs were lower than men’s, and many had the chance to work in the camps, for example in the kitchens, where they received extra food rations as payment. Women are also known to have shown solidarity toward one another by sharing any extra food they managed to obtain with their fellow prisoners.

Women in the camps often displayed resourcefulness, seeking to improve their situation by appealing to the goodwill of guards and, when necessary, by forging alliances even with the enemy. Conditions varied greatly between different prison camps depending on the attitude of the guards; some tried to help, while others were extremely strict.

After the war

Due to the unprecedented number of prisoners, 145 state criminal courts were established across Finland to issue sentences to the Reds. A total of 75,575 individuals appeared before the courts, of which 5,533 were women. The sentences for women were mostly lenient. More than one in four women were fully acquitted of charges. They were considered either completely innocent refugees or had assisted the Red Guards in such a minor way that a sentence was deemed unnecessary. However, the law was not the same for everyone, as some state criminal courts issued harsher sentences than others. The majority of women were convicted of aiding and abetting treason, and the most common punishment was a 2–3-year conditional sentence. This meant they were released but had to live without reproach for the next five years in order to avoid the full prison sentence. Only one woman was sentenced to death in court, but she was pardoned before the sentence was carried out. Anyone sentenced in a state criminal court also lost their civil rights for a period of time. This included, among other things, the loss of voting rights.

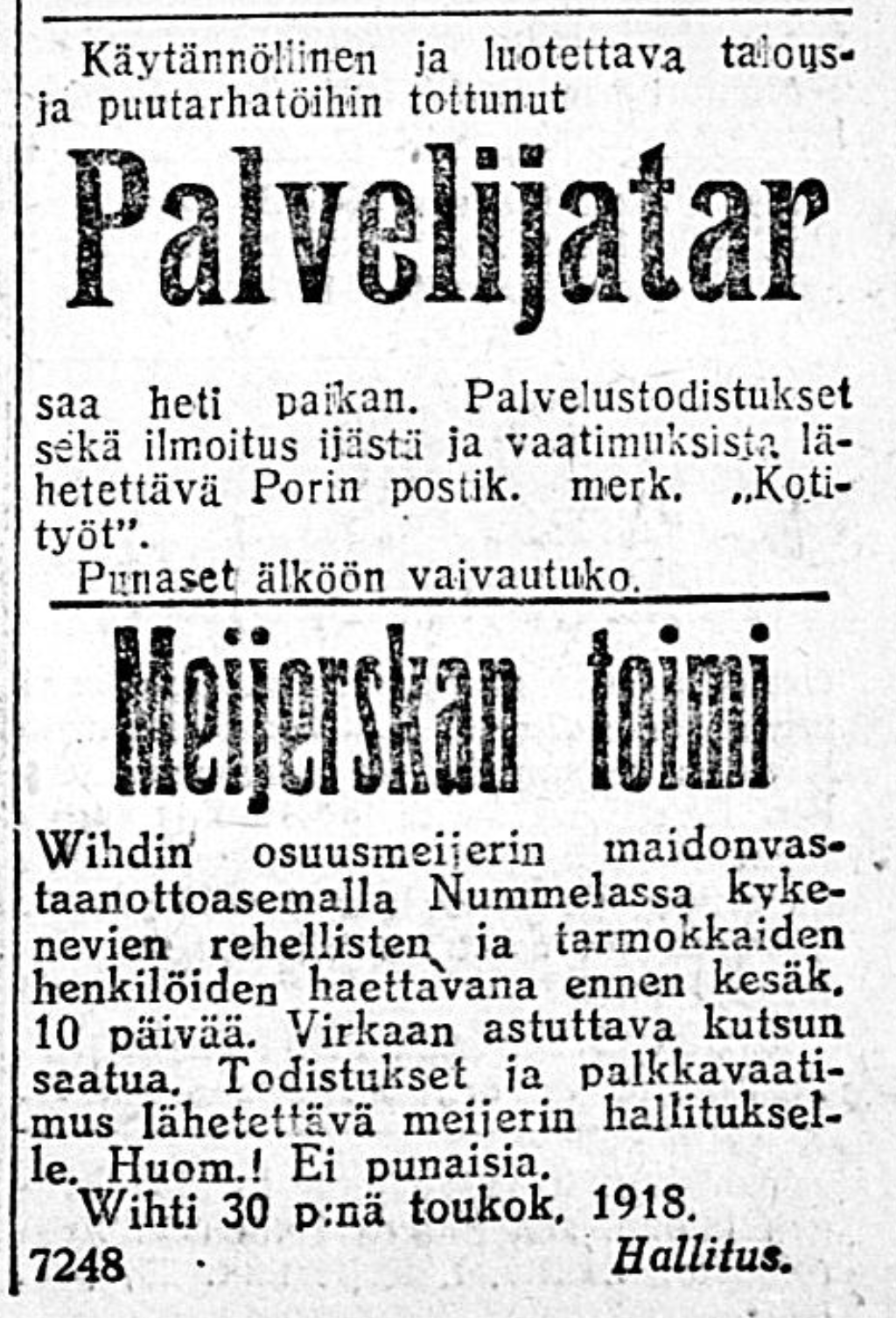

Red women were not only sentenced in court. The surrounding White society also condemned them after the war, and especially in smaller communities, returning to daily life was difficult. In those areas, everyone knew each other’s political affiliations, and rebellious actions were hard to forgive. Women who had worked as maids and servants in households were particularly looked down upon, and they were often not accepted back into their previous jobs in the same household. Job advertisements in the summer and fall of 1918 emphasized that “Red women” (a derogatory term for those associated with the Reds) would not be hired. Returning to factories was easier, as skilled workers were in demand there.

The war did not spare women, even as civilians. Many families were torn apart when men died, fled across the eastern border, or were imprisoned, leaving women to care for the children on their own. Society became divided. The unequal treatment was evident in the fact that widows of White soldiers were quickly granted state pensions after the war, but the widows of the red side were not considered entitled to the same support. Instead, they had to rely on discretionary poor relief. Poor relief was much smaller than the pension, and those who received it lost their right to vote. In order to survive daily life, women left to support their families on their own had to be resourceful and rely on the help of their close circles.

The Civil War was a traumatic experience for women on both the White and Red sides. The grief of losing loved ones was overwhelming. On the red side, this was compounded by shame, and many remained silent about their experiences for decades, or for the rest of their lives.