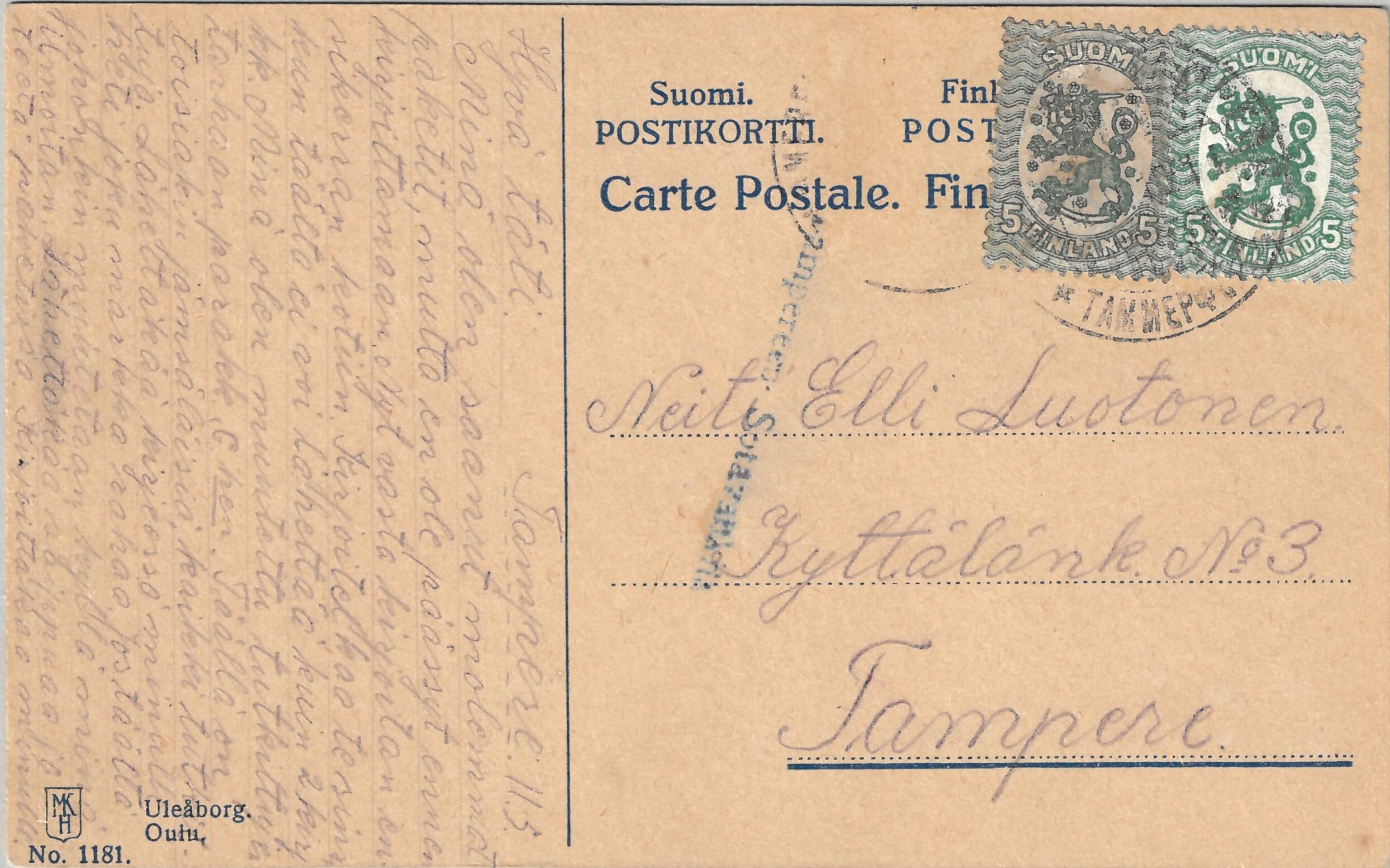

The Civil War separated tens of thousands of Finns from their families. Communication between home and the frontlines was primarily maintained through letters and postcards. The White Army organized a rudimentary field mail system, while in areas controlled by the Reds letters were sent through ordinary civilian channels. Censorship, typical of wartime letters, remained limited during the Finnish Civil War. Despite challenging circumstances, letters usually reached their destination, albeit sometimes with severe delays. The excerpts presented in this article are all from letters and postcards from the period. They were written by both Red and White soldiers as well as civilians. The fates of the writers have been attempted to be uncovered, but sometimes only anonymous fragments of letters remain.

Letters from the Civil War as Historical Sources

Through letters one can get close to the thoughts and emotions that the writers had during specific moments of the war, without hindsight formed decades later. Naturally, letters were intended to be read by another person, and the relationship between the correspondents influenced what was written and how. The value of letters may not necessarily lie in the precise historical events of the war, which have mostly been revealed through other sources. For instance, descriptions of battles in the letters can be quite biased and emotionally guided, depending on the relationship between the correspondents. From the perspective of the history of experiences, however, the fact that the writers’ understanding of events was distorted or incomplete is not an issue. What matters is the kind of experiences individuals had had and how they personally experienced the war. Letters reveal thousands of personal stories. They also tell us what matters were considered important or appropriate to share at the time.

Although many letters did not directly describe battles, the effects of war can be seen in all of them. Correspondence was generally between soldiers and civilians, so the letters also revealed experiences and thoughts from the home front. Due to the rarity of censorship, the letters presented both arguments for and against the war and uncertainty about victory. In the absence of official censorship, the content of the letters was still guided by varying levels of self-censorship, the writer’s tendency to select and modify how they present their thoughts. For instance, the situation on the front lines could have been presented more favourably than the writer truly saw it, so as not to worry loved ones too much. However, one must keep in mind that due to the slow flow of information, contemporaries might also have been completely unaware of the true course of the war. For example, there was great uncertainty on both sides about the situation during the Battle of Tampere. The depth of the letters was also influenced by simpler factors, such as haste and availability of paper. This is most evident in postcards from the time of the prison camps, where the limited writing space of small cards was crammed full of text.

“I wonder how many will return” – Frontline Battle Phase

Enthusiasm for the war was high on both sides especially when everything was new. Maakko Snokko, a soldier of the Lapua Civil Guard, was among the first in the battlefields of Vilppula. There, tens of kilometres north of Tampere, the frontline was beginning to form. He informed his family on February 3: “Life here is fun: singing, dancing, and fighting. Everything is all right [“all right” is written in English], the boys are well.” So far, the “battles” on the Vilppula front had merely been exchanges of gunfire on the previous day, with no harm done to the White soldiers. No-one had fallen in battle, and the spirit of adventure was undiminished. The merriment included alcohol, which the frontline commander banned the next day, however.

Life here is fun: singing, dancing, and fighting. Everything is all right, the boys are well.

Civil Guard soldier Maakko Snokko writing home 3 Feb 1918

Even though the war cast a shadow over everyday life in Tampere, efforts were made to keep things cheerful. Red Guard soldiers accommodated in the city spent time with local girls. One such encounter was between Hilma Lindström and Ilmari Lahtinen, a soldier of the Helsinki dockworkers battalion. As promised, miss Lindström wrote to the Red Guard soldier after he had been sent to the front on February 28: “Our time together passed pleasantly, though it could have been even more enjoyable, but your behaviour was too inappropriate, although perhaps we too were at fault. But that can be forgiven on both sides.” She had already spent an evening with the next group of “boys from Helsinki” who were passing through the city, but the possible fate of her correspondent, that being death on the battlefield, made her upset. Nevertheless, she considered fun as the best remedy for the unfortunate state of the world: “I’m always caught up in the excitement every evening and don’t really think seriously about this world, since worrying won’t make it any better anyway.”

The accommodations of the Red Guard troops and their occasionally lively activities in the city did not please everyone. The provisioning of the guards took precedence over that of the less fortunate. Oskari, who signed his letter with just his first name, complained to his mother about the situation on March 2: “If Tilda also joins the Women’s Red Guard, the food supply will become even scarcer. You can’t get much from the municipal kitchen here either. Those Reds will soon devour the whole of Tampere.” Oskari had gone to a food kitchen, but now that was prevented: “Only Red Guards were allowed inside.” Municipal kitchen number 2 was turned into a new dining hall for the Red Guard when more troops were being stationed in the strategically important city. The rumour of the Whites’ impending advance from Lavia to Suodenniemi perhaps instilled hope of change in the situation, but Oskari still advised his mother to come to Tampere to escape the fighting.

Letters served as a way to get information directly from the frontlines, as the press was known to spread propaganda and information about the fallen was often vague. The desire for information from loved ones can be seen, for example, in a letter dated March 25th from Tampere, which a curious father sent to his son, a Red Guard soldier: “How are you doing, and what’s happening there, though I do know that at the front, one is not daydreaming but showing one’s bravery.” Great pride and high expectations, as well as the idea of war as a noble endeavour, showed in the father’s words: “In your young heart, there are probably many useful hopes for the future of our homeland. Try to act precisely in all your tasks, precision makes a man distinguished, and act in a way that even death, if it comes upon you, would not bring joy to the enemy.” The father, due to his age, couldn’t join the fight for the labour movement, but his thoughts were always with his beloved son: “My ideals are fighting alongside you, following you everywhere.”

In your young heart, there are probably many useful hopes for the future of our homeland. Try to act precisely in all your tasks, precision makes a man distinguished, and act in a way that even death, if it comes upon you, would not bring joy to the enemy.

A father writing to his son in the Red Guard 15 March 1918

Concern for loved ones even infiltrated dreams, and several soldiers’ family members wrote of suffering from either insomnia or, conversely, nightmares. Martta Linna wrote to her brother August, who belonged to the Tampere Red Guard, on March 4. She had visited their parents in Kangasala and informed her brother about their parents’ situation: “Father already dreamt that you had said your goodbyes and they had thought that you must have been wounded or killed, but I just said that news will come if that happens.” Additionally, “Mother has been not eating at all.” The sister asked her brother to take some leave so that their parents could be reassured he was fine. Requesting to take leave was a common theme in letters sent from home to Red Guard soldiers. This family’s acquaintances were all occupied by the war: as cooks of the Guard, as members of the Womens Red Guard, and with the Red Cross. The echoes of the front-line battles resounded in Kangasala, which their parents nervously listened to in the evenings.

In mid-March, the Whites launched a major offensive towards Tampere. Among their ranks was Heikki Lindfors, a 23-year-old astronomer who, after graduating from Tampere Lyceum, had ended up working at the Sodankylä Observatory. A sense of duty compelled him to join the White Army, as his mother and brother were trapped on the side of the country controlled by the Reds. His enthusiasm grew he approached battle on March 13th: “On the Häme front, we then arrived at a threatened place where the thunder of cannons and the roar of machine guns greeted us.” In his messages Heikki did not admit that the dangers of war would discourage him: “The front-line position is fun because you always get to participate when volunteers are asked for some adventure.” A sense of adventure and perceiving war as a masculine experience were reasons for many to volunteer. War had been romanticized during times of peace. Lindfors even quoted stories from The Tales of Ensign Stål, an epic poem about the Finnish War of 1808-09. “It develops your nerves,” he said about war. Despite some shortages of food and sleep, he was not disheartened. However, Lindfors did not describe everything to his family: “Yes, you do see a lot of unpleasant things, but C’est la guerre!” [Such is war!]. This was a form of self-censorship and maintaining image: the brutality and destruction of war were pushed aside with a humorous remark, so as not to tarnish the construction of his own heroic narrative too much. The devastation caused by the opposing side was sometimes described in detail in letters, but the wrongdoings of one’s own side were scarcely mentioned. Lindfors did not live to see the liberation of his hometown. The scientist fell in battle on March 28 in Tampere. In his obituary, he was likened to Sven Dufva, a heroic soldier in The Tales of Ensign Stål.

“Now we’re heading to Tampere” – The Battle for Tampere

The White forces’ attack advanced swiftly, and by the end of March, Tampere was encircled. The most confident White soldiers already informed their homes that their next letter would come from Tampere. Within the siege, the hope of the bourgeoisie residents rose, but the Red Guard’s home searches turned letters into incriminating material that was destroyed out of fear of punishment. There are not many letters from the Reds’ side written or preserved during the Tampere siege either. Letters began serving as final farewells in the face of near-certain death.

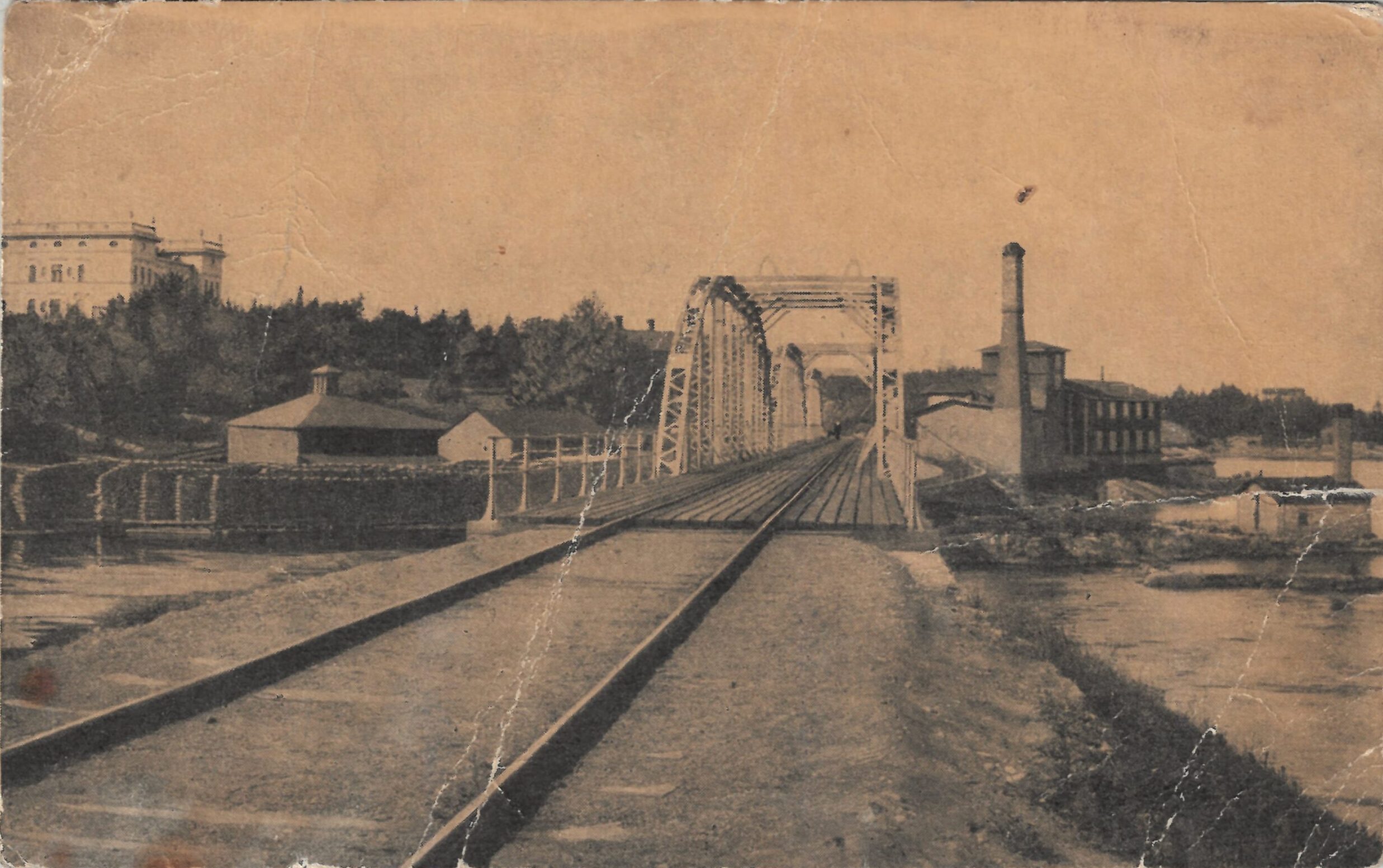

Among the confident White ranks was Voitto Vuorinen, 25-year-old leader of a machine gun squad. On March 31st, he wrote to his family in Keuruu after narrowly surviving bullets that hit his machine gun. The destruction caused by the Reds and the lack of humanity made him “melancholic.” Besides murdered white sympathizers, the damage caused by the Red Guard to property also shocked White writers. While the damage caused by White forces was a necessary evil, Vuorinen was saddened “[…] to let the boys shoot it [Tampere], as I consider it almost a second home.” According to Vuorinen, the Tampere Reds would have already surrendered, “[…] but the Reds from Turku and Viipuri won’t give up.”

One of the last letters sent from inside the siege of Tampere was on March 25th from a woman named Ida to Red Guard soldier Arvo Lehtonen. Artillery fire created such a noise that no Tampere residents had ever heard the like: “Here, there are fierce battles, we woke up on Sunday morning, and it[artillery] was banging so loudly that it was a bit scary. Life feels very oppressive. I miss you so much that I can’t even explain it rationally. When I see those troops rushing forward with rifles, I remember you, heroes of our age, fighting for your freedom. The sound of cannon fire is heard again.” The impending fighting on the city’s borders shook Ida, who had previously been certain of the Reds’ victory.

Things are so chaotic here, the ‘butchers’ are approaching the city... My faith is starting to waver already, maybe we’ll still win. I’m a bit sick from these things...if I’m alive, I hope we’ll meet again.

Ida to Arvo serving in the Red Guard, 23 March 1918

The Red-controlled press had presented an overly optimistic picture of the situation. Like many other residents of working-class neighbourhoods in shoddy wooden houses, she prepared to flee her home: “Things are so chaotic here, the ‘butchers’ [Red name for the Whites] are approaching the city. I also packed my belongings in case I need to leave. It feels wrong to leave my home, and I’ve always said that they won’t come here, but they might. My faith is starting to waver already, maybe we’ll still win. I’m a bit sick from these things.” In Ida’s mind, uncertainty no longer pertained only to the outcome of the war but also whether she herself would survive: “[…] if I’m alive, I hope we’ll meet again.”

The Red Guard attempted to break the Tampere siege from the outside, attempting an attack from the south. On the easternmost wing of the offensive, in Metsäkansa, a Red Guardsman found himself in his first battle: “It’s Easter Sunday now as I’m writing this letter, but we don’t have any celebration here, just the booming of cannons, machine guns, and rifles, which is something fun too.” The writing of the letter was cut short when the order to attack came, and it continued on the battlefield: “We’re trying to reach a certain mansion. […] This letter is written in the forest, behind that rock where we rested and checked our positions.” Action brought the much-wanted change from guard duties: “Now I know what war is like, and I do find it exciting.” The letter has been torn, and the writer’s identity remains unknown. The Red attack did not lead to results, and the siege of Tampere held. In the midst of battle, the situation might have appeared good in that moment in the eyes of a single Red soldier. During a time when propaganda ruled and the movement of information was slow, an individual’s perception of the war situation was largely based on their own experienced and witnessed information. Between false reporting and wild rumours, there was no chance for a foot soldier to ascertain the pure truth. As pne writer summarized: “One person says this, another says that, and everyone claims to speak the truth.”

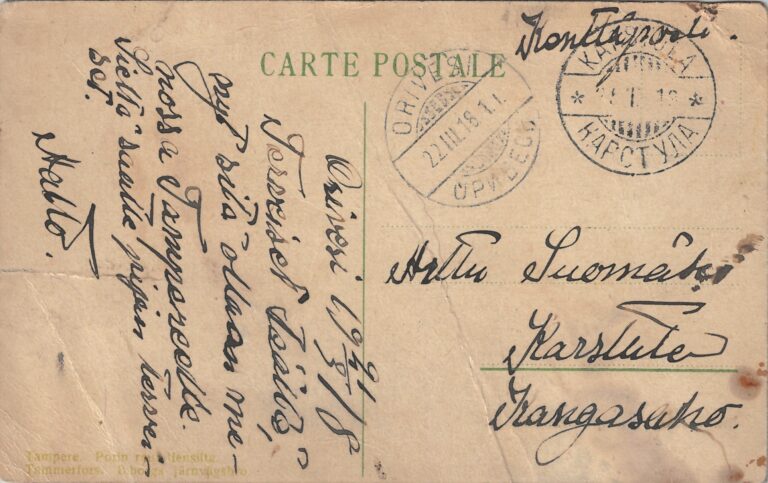

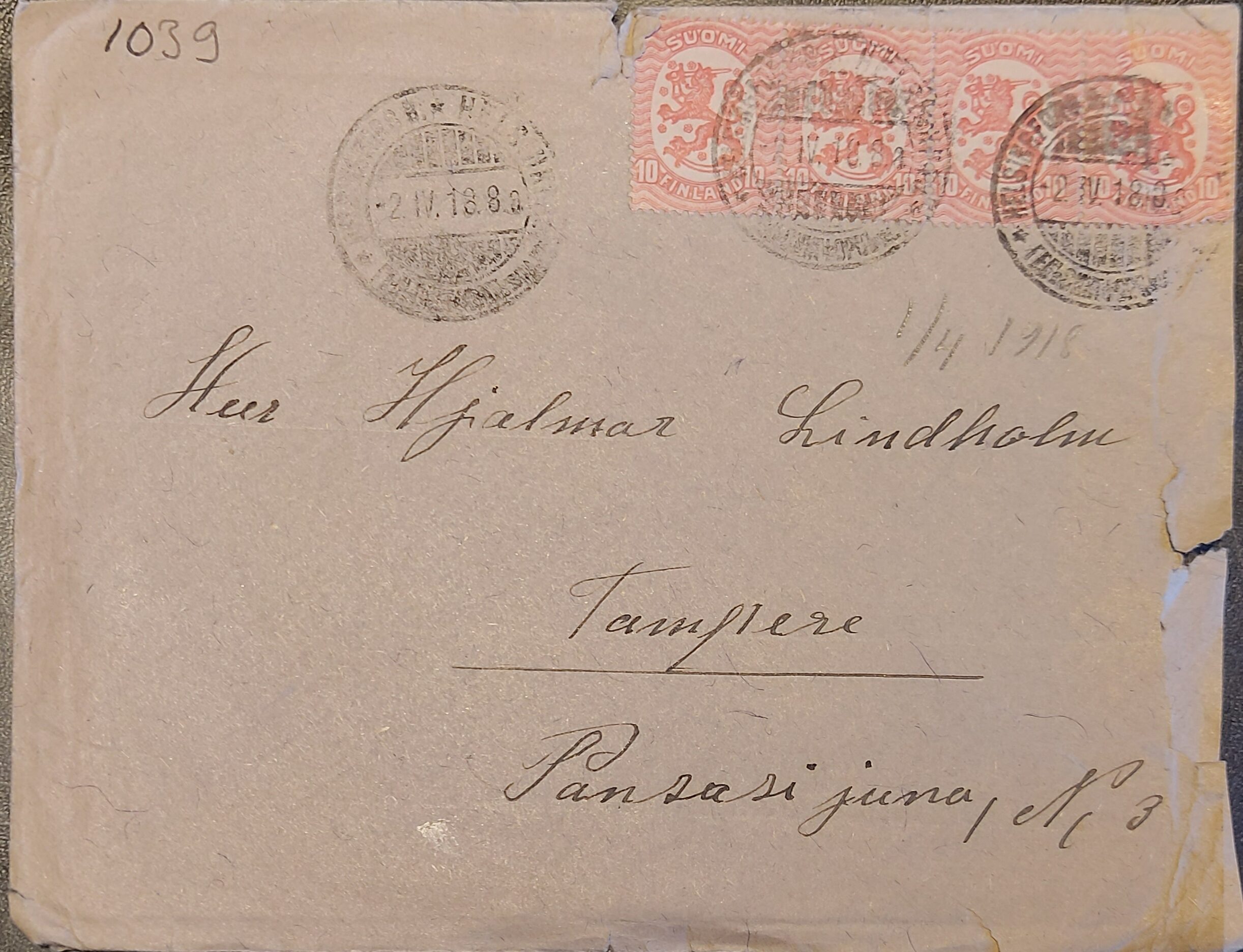

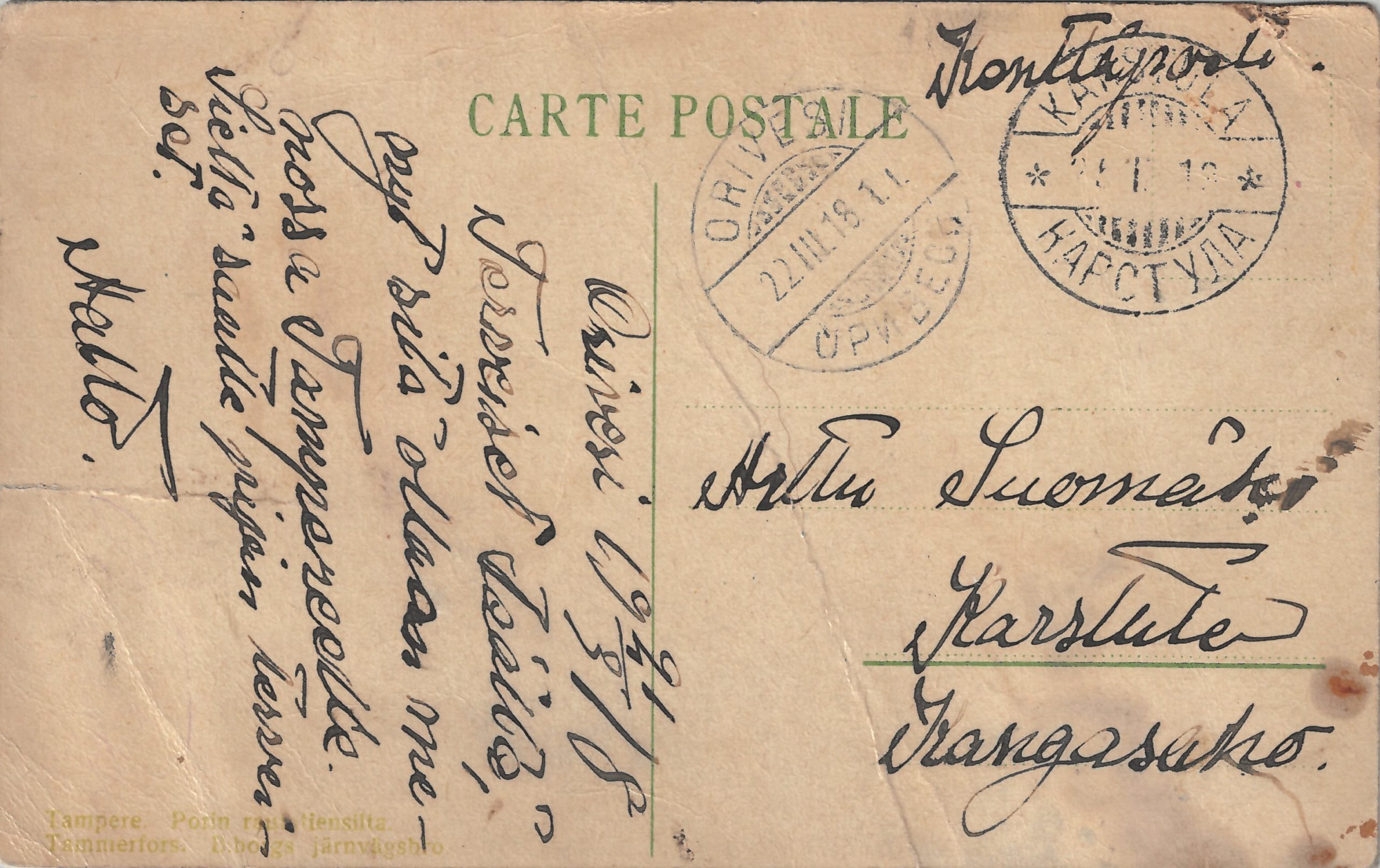

Elsewhere in the Red-controlled area, news of Tampere’s situation was reported with significant delay, if anything was known at all, leaving many to mere conjecture. A letter addressed to Hjalmar Lindholm, a member of the crew of the Red’s armoured train no. 3, which was trapped in Tampere, on April 1st, pondered the city’s fate: “All sorts of rumours have been circulating about the events on the Tampere side, sometimes the ‘butchers’ are supposedly in Hämeenlinna and other times in Riihimäki.” Despite everything, there was some good news as well, as Lindholm’s brother had gotten married. In the confusing situation, the sender didn’t even know that Lindholm had already been transferred to armoured train no. 4 and was no longer in Tampere. Red letters sent to Tampere indicate that some had no idea that the battles had already reached the city. Some of the White letters, on the other hand, prematurely celebrated the capture of the city.

If this is my final journey to Tampere, I bid farewell and hope that you will remember me with joy...Facing death with joy for the sake of the fatherland. Warm regards to everyone. Voitto.

White soldier Voitto Vuorinen to his family 2 April 1918

On April 2, the White soldier Voitto Vuorinen informed his family, having seen “confidential documents and studied the plan.” According to the plan, a major attack on the city centre would begin on April 3. Vuorinen himself noted that he was writing to his family as if he was “sentenced to death.” He felt that no sacrifice was too great, because Tampere would be their “last tough nut to crack.” Despite his sombre words, Vuorinen assured his loved ones that he was in good spirits. “If this is my final journey to Tampere, I bid farewell and hope that you will remember me with joy.” He knew that the White army would not avhieve victory without sacrifice. April 3 indeed proved to be a bloody day, with at least 230 White attackers dead. One of them was Vuorinen himself, whose message truly remained his last: “Facing death with joy for the sake of the fatherland. Warm regards to everyone. Voitto.” The letter was found in the pocket of the fallen Civil Guard soldier.

Prison Camp Letters

The final Red defenders of Tampere surrendered on April 6. The most difficult and decisive battle of the war had concluded with White victory, and the city’s bourgeoisie rejoiced at their liberators. For many Reds, however, the suffering continued in prison camps. This endured longer than the fighting and led to many dead. Letters remained the most crucial means of communication for prisoners separated from the rest of the world by barbed wire fences.

...as our freedom is gone, oh, how happy I was to see you, even if only through the barbed wire fence.

Red prisoner Hermanni Humaloja to his wife 21 June 1918

One of the Reds who ended up in the Tampere prison camp was Hermanni Humaloja, a smallholder and a father of one child. Secret letters, which passed through intermediaries, allowed for freer conversation than the open postcards that went through the camp office’s inspection. “From Tampere Prisoner of War camp No. 1 Barrack 6,” the camp on Kalevankangas, Humaloja greeted his wife on June 21: “Another night has passed, and day is breaking, beautiful and clear, the sun gleams, but here we hardly know of the day because we’re as if separated from the rest of the world, as our freedom is gone. Oh, how happy I was to see you, even if only through the barbed wire fence.” As was typical, Humaloja’s concerns were health, sufficiency of food, and waiting for a sentence. However, the outlook he maintained in his letters was always positive considering his circumstances.

Uncertainty about the impending sentence was also present for an unknown prisoner in Tampere’s prison camp, who wrote to his mother on August 10th: “I haven’t written at all as I haven’t had anything to write with. I’m sending this without postage stamps.” The small postcard has received the prison camp’s inspection stamp. The writer hadn’t received any letters himself, but at least his mother’s package had arrived, containing the “best treats” that were consumed “all at once!” The prisoner, writing from the camp hospital, asked his family to write back immediately. Food deliveries from loved ones were a matter of life and death for the prisoners. Especially for the sick and wounded, survival chances were bleak if relying solely on camp rations. Therefore, requesting food parcels was a common theme in prison camp letters.

Conclusion

At times, when reading about the grand-scale history of the Civil War, individuals get lost in the generalized molds of Reds and Whites, or the fallen are reduced to mere numbers in tables. Private letters help us grasp that in the Civil War, it really was a war of individuals against their own countrymen, each with their own views on the war. For some, the chaos was an opportunity to improve the world or a chance to give purpose to their lives. Sometimes, blind hatred towards the opposing side motivated to fight, while at other times, it was simply the need for money to support family. The concerns of civilians encompassed both the danger to loved ones’ lives and the destruction and suffering brought about by the war, especially by the opposing side. Despite some outbursts of ideology and agression, a significant portion of the letters dealt with matters related to daily survival: whether there’s enough money, if you’re alive, when you’ll return home, food running out, trust in God, and expressions of love. The words written into letters on the eve of the Battle of Tampere became the last for many.

Sources for the letters:

Collections of Ari Muhonen

National Archive

National Library

Postal Museum Archive

Labour Archives